The wildfires of the future are already here. Last month, a fire burning in northern California, driven by a record-setting heat wave, a multi-year drought, and stockpiles of ready fuel, created a 40,000-ft-tall cloud of smoke capable of generating its own weather. Scientists normally associate clouds like these with volcanic eruptions, or nuclear explosions.

During the last decade, in the American west, as well as in Australia and Canada, wildfires of a scale hardly thought possible have begun to appear with distressing regularity. Eight of the largest 20 fires in California history have taken place since 2017. Climate change is a key driver of these fires, and as more people live in fire-risk areas, the threat to lives and property grows.

Beyond the human and physical costs, megafires, wildfires that burn more than 100,00 acres of land, impose hundreds of billions of dollars of economic stress, forcing businesses to shut down and sending tourists elsewhere. California’s 2018 wildfires likely cost the state $148.5 billion. Their smoke can cause health problems over hundreds of square miles. They also contribute to climate change, with studies estimating that burning forests have cut into carbon offsets and added millions of tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere—emissions equal to more than twice the reduction caused by California’s decarbonization efforts.

This is a big problem, and any big problem in California will attract two things: Hollywood treatments and venture capital money. Wildfires are no exception. Convective Capital, new investment fund backed by a group of successful entrepreneurs has raised $35 million to invest in businesses they call “firetech.”

How to throw money at a fire

Bill Clerico, Convective’s managing partner, sold the company he founded, WePay, to JPMorgan in 2017 for $400 million. That same year he and his wife purchased a home in Mendocino County, several hours north of San Francisco. The next year, a wildfire burned 90 acres nearby. He had trouble getting insurance for his home. He became a volunteer firefighter, joking that as a rookie his main role is directing traffic.

The threat of fire became a “shadow in my life,” he says, and he wondered if new technology could help solve the problem. While megafires will require public action from government agencies, land managers, and NGOs, he sees better tools as a way to increase their effectiveness.

The Inflation Reduction Act and the infrastructure legislation enacted by Congress in August of 2022 included some $5 billion in wildfire mitigation funding, mainly to remove potential fuel—fallen logs, dead brush, accumulated leaves, and pine needles—from at-risk areas. The US Forest Service estimates that $50 billion is needed.

“Tech needs to run in parallel and amplify those efforts—make it 20% cheaper and do it 20% faster, and we’ve now taken that $5 billion and made it [equivalent to spending] $7-8 billion,” Clerico says.

Convective has begun investing in firms that are building robots to perform the controlled burns that are essential to avoiding megafires, and in autonomous drones that can drop fire suppressants from above. Its companies are using satellites and drones to give forest managers better information to prioritize their limited resources.

An earlier warning for fire danger

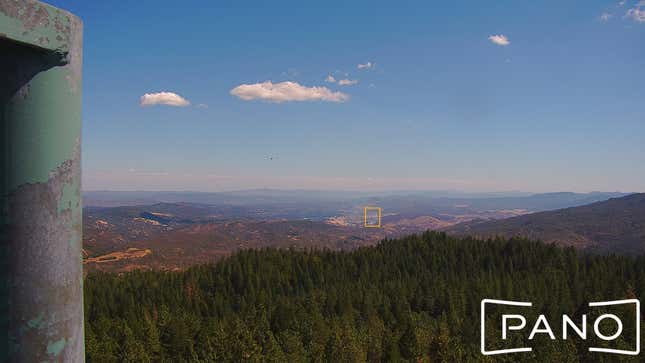

One of Convective’s investments, Pano, has disrupted the old-fashioned fire tower. It uses off-the-shelf technology to put panoramic cameras on mountaintops, links them to a communication network, and uses machine learning to spot smoke and warn fire agencies and utilities. The goal, founder Sonia Kastner says, is to speed the adoption of new firefighting techniques that emphasize using the heavy artillery of firefighting, like aircraft, well before a fire spreads out of control.

The company has deployed its technology in five US states and two in Australia. Customers include fire agencies, but also utility companies that need to monitor thousands of miles of transmission lines in rural areas, which can both cause fires and be shut down by them. Portland General Electric (PGE), the largest utility in Oregon, uses 26 Pano stations in high-risk areas that include some 30,000 businesses and households, and 1,800 miles of electrical lines.

“Pano cameras have identified a number of fires, triggered things much faster at fire departments than ways we might have responded in the past,” says Larry Bekkedahl, a senior vice president who works on advanced technology at PGE.

Phil Schneider, the fire chief in Sandy, Oregon, was given access to test PGE’s system of Pano cameras. On the first day, he received a text alert about what would become a four-alarm wildland fire, minutes before 911 dispatchers contacted him. He says the system can save time for firefighters trying to confirm tips in remote areas, speed evacuation, and also guide responders when fires are detected. It can even help firefighters save resources by deciding not to pursue a fire.

“It is a fact that we are seeing hotter, drier, and quicker growing fires than I’ve ever seen in my history,” says Schneider, who has spent 46 years at the department. He’s pleased with Pano and the idea of new tools for fighting wildfires, but emphasized that people need to make sure they are taking the right steps to protect their property and prepare for fire season, like creating a defensible area and having an evacuation plan.

Megafires can be stopped

“Unlike other climate driven disasters, we have the agency to fix this,” Matt Weiner, the CEO of Megafire Action, says. “Messaging to the public that this is a solvable problem is a key issue. No one is going to demand you solve the problem until it is solvable.”

Megafire Action is a NGO that lobbies for government action against wildfires. Its primary goal is urging policymakers to reverse the mistake made a century ago when American governments halted indigenous practices of using controlled or prescribed fires to prevent uncontrollable maelstroms in the future.

Without regular burns, fuel has built up in these wildlands, making preventative fires difficult. “Because we have taken fire out of these landscapes, they are not ready to support prescribed fire in any meaningful way right now and it’s going to take a lot of work to get them there,” Weiner says.

That entails the removal of more fuel from forests, and reforms at institutions like the National Forest Service to achieve that on the necessary scale. The organization also wants to see more federal investment in science that could improve wildfire defense, including better understanding how to model the behavior of fires.

Many of Convective’s partners are also backers of Megafire Action, including the organization’s chair, George Whitesides, the former CEO of Virgin Galactic, and Ilya Volodarsky, an entrepreneur who now operates Wildfire.org, a non-profit that develops software to solve bureaucratic delays in fire mitigation, which requires complex environmental reviews and permitting.

“As I started to get smart on wildfire, I kept running into them,” Clerico says. It speaks to the relatively small world of concern for a problem that has only emerged in recent decades. Now, Convective—named after the physics term for heat transfer—will work to bridge the gap between technology and the organizations trying to solve it. While the fund is small, he hopes its purpose-driven venture capital can attract larger pools of capital interested in climate investing.

“Institutional forestry people might be skeptical, technologists are skeptical of the market size and the buyers here,” Clerico says. “It reminds me of fintech in 2008 when I was starting WePay—a ground that technology had not touched.”